29 June 2005

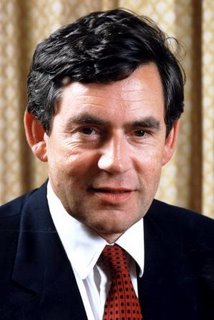

Speech by Rt. Hon. Dr. Gordon Brown MP, Chancellor of the Exchequer at the annual lecture to UNICEF

From debt relief to empowerment

I am honoured and humbled to deliver the annual lecture of UNICEF, which for more than half a century has been serving the world in a global crusade for justice for children:

founded on a lasting commitment to ensure, in every part of the world, children fed, children taught, children saved and children empowered for their future;

driven forward by a timeless philosophy that not just some children but all children should have the best possible start in life; and

today the living embodiment of the ideal that hope should never die even in the hardest and harshest of places.

And I am especially privileged to speak in the presence of your Chairman and I particularly want to thank him and our UNICEF ambassadors, whose leadership has been truly inspirational.

And I am doubly privileged to speak to you about children and global poverty only days before what I believe can be a history-making G8 Summit at Gleneagles and in advance of the special UN Summit in New York in September, where the ideal of a world free of poverty and deprivation - that UNICEF holds precious - will be at the vital centre of deliberations and decisions.

And today I want to consider with you the long journey we are on, to examine with you how far we have come and how much we have yet to achieve, and to discuss with you the potential that now exists for a new relationship between rich countries and poor - what can grow into a new covenant that builds upon the need for debt relief, aid and trade justice and has as its long term objective the empowerment of the powerless and the poor to the benefit of the whole world?

Our starting point - the foundation of the work of UNICEF - is our anger that across the world 30,000 children will die unnecessarily today and every day until we act. Each one a life, a child, a priceless hope; but now dying - a life, a child, a priceless hope lost.

And who is not angry also that tomorrow morning around the world 110 million children will not be able to go to school and - as UNICEF have shown – it is girls who suffer most from this waste of potential, this denial of human dignity.

And it should anger us, move us and then drive us on to action that, on present rates of progress in sub-Saharan Africa, the Millennium Goal for even basic schooling for every child will not be achieved by 2015, not even achieved by 2115, not achieved until 2129 – not for more than a whole hundred years. Basic schooling not achieved for this generation of children, not for the next generation of children not even generations after that.

The Millennium Goal of eliminating avoidable child deaths will not be achieved in ten years by 2015, as promised, but not for 100 years, not until 2115. And the Millennium Goal of cutting poverty by half will not be achieved in 2015 but not until at least 2150.

If I could take you to the villages I visited earlier this year in Tanzania, Mozambique, Kenya in Southern Africa I would show you and convince even the most sceptical of the need to act

The conditions I saw in those villages is a standing affront to our common humanity – a reproach to all of us.

Young children often called upon to care for adults with HIV/AIDS. Young children who should themselves be cared for caring for those who can no longer care for them. Children being asked to bear burdens no child should be asked to carry, to bear the burden of diseases that in this country – because we have the drugs and treatments - are curable, but cannot be cured without them. Burdened by the knowledge that so many of their family and friends have a life span that is not three score years and ten - but who are living lives cut short tragically by poverty and disease.

Confronted by such suffering it is right that we are moved to act.

This organisation UNICEF is founded on an explicit understanding of our shared responsibilities as adults to the children of the world.

What differentiates adults from children is that we as adults have responsibilities that for us are an unconditional duty to care.

Is not the enduring truth at the centre of all UNICEF stands for - that every child is precious, every child is unique, every child – perhaps especially the weakest, the frailest, the most vulnerable – is special and must count?

And that every single child deserves the chance to bridge the gap between what they are today and what they have it in themselves to become.

So our national and international duty as the G8 approaches – a duty which Tony Blair, Hilary Benn and I are committed to – is to ensure that each child has the chance to make the most of their potential, to empower every child with, in the words of Amartya Sen, "the substantive freedoms – the capabilities – to choose a life one has reason to value".

That is why, to relieve immediately the suffering we see and to meet the Millennium Development Goals, we start with debt relief – to remove the burdens of unpayable debts from the past; aid – to invest in people for the future; and trade, to enable every country to make its way in the world.

Together and for years we have fought for debt relief - and this year we are finally delivering –100 per cent relief to the poorest countries in the world: a $55 billion write off of multilateral debt, $40 billion immediately – debts to the 38 poorest countries that would, under our proposals, be written off; debts to another 28 countries that it is Britain's intention to write off and for which we will continue to seek world wide support.

Removing the burden of unpayable debt is a necessary first step to the empowerment of people.

An empowerment that can be achieved through health, education and economic development.

So the next step is to deliver a doubling of aid.

In the last few weeks European Union Finance and Development Ministers have agreed a historic increase - from the $40 billion it was last year to the $80 billion it will be by 2010.

For thirty years governments refused to honour the agreements proposed by the Pearson Commission to raise aid to 0.7 per cent of their national income.

Now country by country in Europe – from Britain, France and Spain now to Italy and Germany, as well as Belgium, Ireland and Finland – a 0.7 per cent timetable has been announced: 13 countries now committed to the target of 0.7 per cent.

And moving forward too is the idea of frontloading this aid and delivering it quicker through the International Finance Facility.

And when Finance Ministers met three weeks ago we agreed trade justice had to be advanced so that poor countries can participate in the global economy on fair terms. We agreed that a timetable should be set to end export subsidies; the poorest countries should be able to decide their own trade reforms, rather than be directed from outside; and help with capacity in trade had to be offered.

And as we move from Gleneagles G8, to the UN Special Summit in New York in September, to the WTO talks in Hong Kong in December we will do everything in our power as individuals, as nations and as nations working together to secure the completion of debt relief, the doubling of global aid and trade justice.

In the last few weeks and months we have come a long way because - this year, 2005 – we will achieve 100 per cent debt relief for the first time. A long way because this year 2005 an agreement that aid from Europe is to be doubled - 40 billion more by 2010. A long way because - this year commits the world for the first time to treat all aids sufferers by 2010. A long way because - this year for the first time ministers have demanded a timetable. For the end to trade subsidies and recognise countries should be allowed to decide their own trade reforms.

And I want to thank UNICEF and people from all faiths, churches and non-governmental organisations who have made it your mission to challenge governments to implement these millennium development goals.

Indeed when the history of the movement to eradicate world poverty is written the role you, UNICEF, and your sister organisations have played will be a proud and historic chapter, the beginning of the story of making poverty history.

Because of you we have come a long way.

But, as you tell us also, we have a long way still to go.

And the next steps on our journey, building upon debt relief and aid are the theme of my speech today - that our ultimate objective is the empowerment of countries, communities and people.

Instead of leaving people dependent and powerless, stripped of their dignity and unable to realise their potential, our aim - UNICEF's aim – is that young people are encouraged, enabled and - yes empowered - to make the most of their talents and their lives.

And I want to set out today how this call for empowerment requires nothing short of a new relationship between rich countries and poor countries:

A new covenant founded not on the old colonialism, nor on post-colonial dependency; but on a partnership of equals. A partnership, as the Commission for Africa states, of "solidarity and mutual support, founded in a common humanity".

A covenant that not only hears the voices of the poor but, actively, ensures power and opportunity in the hands of peoples for too long denied their rightful place.

A covenant for trade justice and economic social and political empowerment that is therefore more than the old familiar contracts negotiated between donors and recipients, between the powerful and the powerless, and demands commitments that are not just for today and tomorrow but crosses the generations and is for generations to come.

A covenant which - because it is driven forward by both the duties of the rich and the empowerment of the poor - is rooted not just in shared interests but in shared values, the essential belief, in the words of the UN Declaration of Human Rights, that "all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights".

A covenant at the heart of which is the empowerment which comes from fair trade and economic development providing opportunity even to the poorest village and the empowerment which comes from free education and free health care.

Let me explain what I believe is the foundation of the new covenant that recognises the responsibilities each of us have for one another in one universe.

A few months ago the tsunami showed the world not only the power of nature to destroy but the power of humanity to heal, to comfort and to build anew.

Extraordinary spontaneous support, financially and physically, to meet the needs of others whose names we did not know and whom we will never meet

But just about everything we witness across the world today from the effects of global trade to the threat of global terrorism symbolises just how closely and irrevocably people now see the fortunes of even the poorest people in the poorest countries y now bound together to the fate of the richest people in the richest parts of the world.

It is a world where people who are strangers – one to another – are coming to understand their shared interests, common needs, mutual responsibilities, and linked destinies, where we come to recognise that each one of us as citizens of the same world, each of us dependent upon the other.

But I do not believe that this enlightened self interest alone explains why millions felt moved to donate to the tsunami appeal, why so many are moved to tears by the death of a child from hunger or disease even in far away places and mourn as if it were a death in the family, why most of us feel, however distantly, the pain of others even when they are thousands of miles from us.

For is there not some impulse even greater than enlightened self interest or even an awareness of our dependence upon each other that moves us as human beings - even human beings in the most comfortable and sheltered of places to empathy - and can move us even to anger at the injustice and inhumanity that blights the lives of people we may never meet and whose names we will never know?

I believe that is it not more than just a set of interests we share in common - a set of values we share in common?

Call it as Lincoln did - the better angels of our nature;

Call it as Winstanley did - the light in man;

Call it as Adam Smith did - the moral sentiment;

Call it as James Q Wilson does - the moral sense.

That people can be dispersed by geography, diverse because of race, differentiated by wealth divided across many faiths and religions - but we have a shared moral sense common to us all.

Even as we are different diverse and often divided, we are not and cannot be moral strangers, for we are members of one moral universe with a shared moral sense common to us all - quite simply that we are human beings of equal value and equal worth. Something that came home to me when I met a 32 year old AIDS victim in Africa, Paolo, who told me he suffered doubly – for his AIDS and the stigma associated with AIDS – yet who said to me “I know I am despised, but are we not brothers”?

And when Christians say, and this is their golden rule: "do to others what you would have them do to you". When Jews say, and this is their golden rule: "what is hateful to you, do not to your fellow man". When Buddhists say their golden rule - "hurt not others in ways that you yourself would find hurtful". Are they not sending out the same message?

When Muslims say: "no one of you is a believer until he desires for his brother that which he desires for himself". When Sikhs say: "treat others as you would be treated yourself”. When Hindus say: "this is the sum of duty: do not do to others what would cause pain if done to you" - are they not, one by one, and in unison, saying to us that you discharge your duties to your fellow human beings - to do to others as you would be done by - not just by ensuring for them a minimum sufficiency nor just by engaging in one off acts of charity but by ensuring that fellow human beings of equal value and equal worth have the freedom and opportunity to develop their potentials.

We discharge our duty to the 12 year old AIDS orphan I described to you not simply by giving her clothes and food but by all of us seeking to make it possible for her to have a real chance of making the most of her talents.

Enlightened self-interest may lead us to propose a contract between rich and poor founded upon our mutual responsibilities because of our interdependence. But it could still be a contract that was not between equals: a contract of giver and receiver, of patron and recipient, leading to conditional charity that leaves people dependent.

But it is our strong sense that human beings are of equal a worth and value that demands a covenant founded on something more than self interest: a covenant that is rooted in our shared values, a covenant that crosses the generations, a covenant , most of all, that empowers the powerless and enables young people and adults to be the best that they can be.

The Ugandan poet Okot P'Bitek writes:

"I have only one request.

I do not ask for money

Although i have need of it,

I do not ask for meat

I have only one request,

And all I ask is

That you remove

The road block

From my path."

Clearly money and food are important, but the essential and enduring truth he highlights is surely right, that in the words of Amartya Sen empowerment “requires the removal of major sources of unfreedom: poverty as well as tyranny, poor economic opportunities as well as systematic social deprivation, neglect of public facilities as well as intolerance or overactivity of repressive states".

Because every time one person’s dignity is diminished by poverty or debt or unfair trade we are all diminished. The issue is not just what we the richest countries can do for the poorest: it is what as partners and equals, not just as donors and recipients, we - rich and poor - can do together

It used to be said

What can we do for Africa

What can we do about Africa,

But these are yesterdays questions

Today's question, the question that matters, is what can Africa, empowered, do for herself?

And today the call of the new South Africa, the aim of the African Union, the moving force of NEPAD, and the stated objectives of a new generation of African leaders is that developing countries take charge of their own destiny and find their own voice as partners not supplicants in global development.

"The time has come for a new birth," Mandela has urged. "We must say there is no obstacle big enough to stop us from bringing about an African renaissance … we know we have it in ourselves as Africans to change all this. We must assert our will to do so." And when Thabo Mbeki states that the African renaissance can only succeed "if its aims and objectives are defined by Africans themselves if we take responsibility for success or failure of our policies", one of the leaders of the new partnership for Africa's development, founded on good government, local accountability and the empowerment of communities and people.

So the empowerment we seek is a million miles away from the colonialism which left people dependent and also a million miles away from the post colonial decades where far from Africa benefiting from what Harold Macmillan called "the winds of change", a pervasive climate of injustice remained.

Nelson Mandela put the challenge ahead best when he said: "When I walked out of prison that was my mission - to liberate the oppressed and the oppressor both.

Some say that has now been achieved. But I know that is not the case.”

As Mandela says: “the truth is that we are not yet free; we have merely achieved the freedom to be free, the right not to be oppressed.

We have not taken the final step of our journey - but the first step on a longer and even more difficult road.

For to be free is not merely to cast off ones chains but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others

The true test of our devotion to freedom is just beginning."

So for us that means not just the liberation of the worlds poorest from their poverty - but a liberation of all the world from the stigma, the scars, the injustice and indeed the danger of poverty and injustice anywhere.

Debt relief should be seen as removing one basic obstacle to the empowerment of the poor - the burdens of the past weighing down the present generation and preventing us planning for the future.

Aid should no longer be seen as a form of charity, compensating people for the failures of the richest countries in the past, but be seen as investment, building capacity so that countries can participate in the world economy and communities and individuals can be fully equipped for the future.

Unfair trade rules do not only prevent poor people from throwing off the shackles of poverty, but shackle poor people and poor communities still further. And so trade justice is not simply about removing the barriers that hurt the poor, but about creating new capacity that empowers poor countries to participate on equal terms in the new economy.

Debt relief and aid are thus the means to an even higher goal, for only a bolder agenda for fair trade and economic development will do most to lift millions out of poverty and empower people to find prosperity with dignity and independence and stand on their own feet.

Think of the Mozambican sugar producer who cannot compete with European sugar beet farmers, because the subsidies Europeans receive enable them to sell more expensive goods at a cheaper price.

Or think of the Ghanaian coca growers who cannot process their beans for chocolate themselves, because tariffs mean its cheaper to process them in Europe – in fact while developing countries produce 90 per cent of the worlds cocoa beans, it is developed countries that produce 90 per cent of the world’s chocolate.

As the Commission for Africa noted and as Hilary Benn reminded us earlier today, rich country barriers and support are “absolutely unacceptable, they are politically antiquated, economically illiterate, environmentally destructive and ethically indefensible. They must go.”

So we cannot any longer ignore what people in the poorest countries will see as our hypocrisy of developed country protectionism. We should be opening our markets and removing trade-distorting subsidies and in particular, doing more to urgently tackle the waste of the common agricultural policy by now setting a date for the end of export subsidies.

But because our aim is to empower communities and individuals through trade, I want us to do more.

A policy to empower must give the freedom to countries and communities to make their own choices and to prevent the most vulnerable from becoming even poorer.

We know that governments in developing countries now recognise the importance of creating the best domestic conditions for trade and commerce – economic stability, sound legal practices, and the deterrence of corruption. But developing countries must also have the flexibility to decide, plan and sequence reforms to their trade policies to fit with their country's own development programmes and not be forced by conditions laid down by us.

And it is not enough to say ‘you're on your own, simply compete’. We have to say ‘we will help you build the capacity to empower you to to trade’. It is not enough to open the door, we must help people cross the threshold.

Today, according to the World Bank, 24 of the world’s poorest countries have neither the infrastructure nor the communications to benefit from 100 per cent access to developed countries markets

While tariff costs are high, transport and communication costs are often higher. Transport costs in Africa - from village to town to city to port – are twice those of Asia. Telecommunication charges from the poorest countries to the USA are five times those of a developed country. And while modern water and sanitation should underpin not just policies for health but policies for development too , even today 40 billion working hours in Africa each year are used up simply collecting and carrying water.

And so it is because new investment in capacity to trade and to secure economic growth is so urgent that the frontloading of aid through our proposed international finance facility is so important.

But empowering people and communities is not simply about building capacity to trade through investment in infrastructure: it must also be about investment in people.

When I visited African countries earlier this year I saw not only the hard unyielding abject relentless grinding poverty I have described but the potential:

the potential of the 40,000 women in Tanzania who are creating businesses through microcredit union

the potential of men and women forming agricultural cooperatives desperate to invest in new crops;

the potential of women at the Tanzanian women’s training centre learning how to create and manage their own small businesses; and

the potential of young people in schools and college, whose ambitions were to be the future engineers, airline pilots, doctors nurses teachers and businessmen and women of Africa.

What I detected was not any lack of ambition but a lack of means to realise these ambitions. What I saw, was not people who had given in and were resigned to be dependent but people with ideas plans and dreams they wished to bring to life.

And the key that unlocks that potential is universal education.

Rightly UNICEF asserts that an education is the fundamental birthright of every child - for an education empowers young people for the future, puts opportunity directly into their hands and is both the very best anti-poverty strategy and the very best economic development programme.

For every additional year of a child’s education, estimated average earnings increase by 11 per cent for each additional year of a mothers education childhood mortality reduced by 8 per cent.

Yet in Tanzania I saw 8, 9, 10, 11 year old children begging to continue in school - but denied the chance because their parents could not pay the fees.

In Mozambique young mothers desperate for their children to go to school waving their pay cheques of £5 a week - and raising their hands as one to complain angrily that they cannot even begin to afford the fees.

In Kenya children chanting free education - but for millions secondary education, beyond their grasp.

I found user fees to be the single biggest peacetime barrier to increasing the number of children in education. With, across sub-Saharan Africa the cost of putting one child through primary school amounting to up to more than a quarter of the annual income of a poor household.

But when we do abolish school fees, we see large numbers of children coming to school:

when in 2003, through aid, Kenya made primary school free in just one week one million children turned up for school for the first time;

when in 2004 fees were abolished in Malawi enrolments increased by 50 per cent; and

in Uganda making education free trebled the numbers of school pupils from 2 million to 6 million.

One answer to those who say aid and debt relief will always be wanted and spent in the wrong way

Because we cannot keep children in school without the long term, year on year investment in buildings, teachers and equipment, action on user fees must be part of a broader government commitment to investment in education - not the funding of the past which was too often halting, sporadic, could not be guaranteed from year to year and too often driven by the strategic interest of donors, but funding which is sustained predictable and which because it is country and community owned – empowers.

Which is why through the predictability and frontloading of long term aid that it brings, I believe the International Finance Facility can play such an important role in enabling the poorest countries to make the long term investment in education for their children that will enable them to break from the vicious cycle of dependency to a virtuous cycle of self-sufficiency.

The total cost of bringing free primary education to all children in Africa and South Asia could be $6.4billion - $5.6 billion to get every child into school and $750 million to abolish fees - more than double what is spent now - but it is perhaps the best and most cost effective investment the world can ever make.

In Mozambique, mothers who have completed five grades of schooling were almost twice as likely to vaccinate their children as less educated mothers. In Zambia, women with a secondary education are around 30 per cent more likely to take their children to a clinic for treatment than women with no education. Educated women are thought to be three times better able to protect themselves against HIV/AIDS than those without education.

Yet we know that in Africa, and across much of the developing world, poverty still has a woman's face.

Women constitute just over 50 per cent of the population in Africa, but 70 per cent of the poor.

But on my visit to Africa I saw clearly that by empowering women - too long held back, but now pressing forward in leadership roles locally and nationally - we can speed development.

As Basrabai of Sewa of the self employed women's association in Gujerat, India said, "at first I was afraid of everyone and everything: my husband, the village Sarpanch, the police. Today I fear no one. I have my own bank account, I am the leader of my village savings group."

And it is women who are now at the centre of building communities.

It was a speech by Gracha Machel, the Gilbert Murray memorial lecture for Oxfam, that brought home to me starkly the difference between Western and African ideas of community - and the unanswerable case for a strategy for empowerment.

We care for people better than you do, Gracha told us and she repeated what Desmond Tutu writes, "Africans have a thing called ubuntu; it is about the essence of being human, it is part of the gift that Africa is going to give the world. We believe that a person is a person through other persons; that my humanity is caught up, bound inextricably in yours. When I dehumanise you, I inevitably dehumanise myself. The solitary human being is a contradiction in terms, and therefore you seek to work for the common good because your humanity comes into its own community in belonging."

So we should listen when Gracha Machel says that caring involves the whole extended family.

Caring not to be seen as a time consuming diversion from work and making money, but at the centre of what it is to be human.

But empowerment to make that idea of caring flourish means putting at the service of communities health care - the medicines, the treatments, the science and technology.

Yet today only 15 per cent of people in sub-Saharan Africa have access to basic health care free from user fees.

Sub-Saharan Africa is the only part of the world to witness child mortality rising. And nearly 5 million children die each year before their fifth birthday.

Sub-Saharan Africa - which accounts for just 12 per cent of the world's population - suffers 42 per cent of young children’s deaths.

The difference between free education and charges is between opportunity offered and opportunity denied. But the difference between free health care and health user charges is between life and death. The evidence is startling and decisive. When Swaziland introduced fees clinic attendance fell by one third and health declined. In other words one in every three families that needed health care went without. When Uganda abolished its user fees clinic attendance rose by over 50 per cent and because health improved people felt empowered.

Ensuring the most basic free health care to the world's poorest has been estimated to cost at least $17 billions each year.

And because, to be effective, health care has to be available on a predictable and sustainable basis and because the internationalisation of research supported by advance purchase schemes offer the way ahead to tackle malaria, new strains of TB and potentially HIV/AIDS. Funding through our International Finance Facility is the way forward for the long term.

Our proposal for the pilot International Finance Facility for immunisation shows what can be done. It starts from the success of the global polio eradication initiative - spearheaded by UNICEF which has cut polio cases by over 99 per cent since 1988, builds upon the extraordinary achievement of the global alliance for vaccines and immunisation –which in only three years has inoculated more than 50 million people, and now proposes borrowing and frontloading 4 billions to pay for immunisation now.

It is a remarkable and startling fact: between now and 2015 that the International Finance Facility for immunisation could, itself, save the lives of 5 million children and adults. In the years after 2015 another 5 million more lives could be saved.

If this is what the International Finance Facility can achieve with one pilot fund and one initiative in one area, think what the international finance facility can achieve not just across the whole of health care but also for education the provision of water and infrastructure and for economic development.

Because free - not paid - health care is the difference between life and death, the free public services I propose are the starting point for empowering millions of people.

And free health care is not just a great western idea dreamed up as the foundation of the European welfare state. Delivering free health care for all is absolutely central - as Gracha Machel makes clear – in bringing to life, for this generation, Africa's enduring ideas of community.

But - and this is my final point - we have learned something even more fundamental in recent years.

Without genuine participation at all levels of society, right down to the grass roots - of women in their communities, of parents in their schools, of men and women in programmes for economic development - change will be skin deep and reform will not be sustained.

The move from the old policy of structural adjustment to the new policy of sustainable development must mean, in practice, the move from policies imposed from above to policies that are not just country led but community owned.

So the political empowerment we seek is, in effect, a new commitment to democracy, founded on participation and accountability, and underpinned by transparency – a strategy for development and thus empowerment that ensures that people can have more control over their own lives.

And this is a million miles away from the school of development thinking in the 60s 70s and 80s which argued that what mattered was not so much deep structures of democratic accountability - of people owning their own future - but strong, often autocratic leadership and externally imposed conditionality, cast as enlightened and modernising.

Without a deep commitment to a participatory democracy - as Condolezza Rice made clear in the Middle East only last week - development is likely to go wrong. And a participatory democracy is best underpinned by a simple requirement that that will become ever more important in the years ahead - transparency. This a call to rich and poor countries alike – as well as to foreign companies and investors - to open our books, be fully transparent and for each of us to account for our actions for all to see.

A new honesty about the effects of our trade protectionism and the tying of aid.

But this is also a call for new openness and transparency in developing countries: people able to see where their money is going, who is doing what and why - the way to root out corruption; and more fundamentally – people and communities empowered to take more control of the decisions that affect their lives and to hold their own governments to account.

In this way we move from the old conditionality imposed on developing countries by donors we can move to a new accountability of developing countries to their own people. And in our international institutions we should also strengthen the voice of the poor.

So today I have set out the long term trade education and health and democratic reforms that are at the heart of the demands from developing countries for genuine empowerment - a modern Marshall Plan for Africa and developing countries.

The original Marshall Plan was always about more than financial aid.

As Marshall said, launching his plan in 1948 "any assistance … government may render in the future should provide a cure rather than a mere palliative … the remedy lies in breaking the vicious circle and restoring the confidence of the people in the economic future of their own countries and of (the continent) as a whole.”

This year in 2005 - a next week at Gleneagles - I believe we will make real progress on the road to empowerment.

As we look ahead to the long term challenges the words of Nelson Mandela are as ever our inspiration.

“I have walked that long road to freedom,” he writes “I have tried not to falter I have made mis-steps along the way but I have discovered the secret that after climbing a great hill one only finds there are still many more hills to climb.”

"I have taken a moment here to rest, to steal a view of the glorious vista that surrounds me to look back on the distance I have come. But i can only rest for a moment - for with freedom comes responsibilities.

And I dare not linger

For my long walk is not yet ended."

Nelson Mandela is telling us our long walk cannot end until we achieve the abiding objective of UNICEF, that free of poverty, injustice, illiteracy and disease every child is empowered to have the best start in life.

The challenge is more urgent than ever.

And so we must not rest relax our efforts nor indulge in any false complacency.

We know the scale of the task, the depth of our responsibility.

For all of us, meeting the millennium challenge is not just a week’s work at G8 but a lifetime’s work that reaches across the world.

And we dare not linger.

No comments:

Post a Comment